Reproductive Justice

The right to make informed decisions about one’s own reproduction is a relatively recent assurance granted to Americans. Although it’s a long-standing right in 2022, it shouldn’t be taken for granted as attacks on access to reproductive care persist in the United States (and elsewhere).

There is a lot to know and learn about reproductive rights and organizing, and it leads us directly to the issues that continue to affect our access to care.

A lil’ history lesson

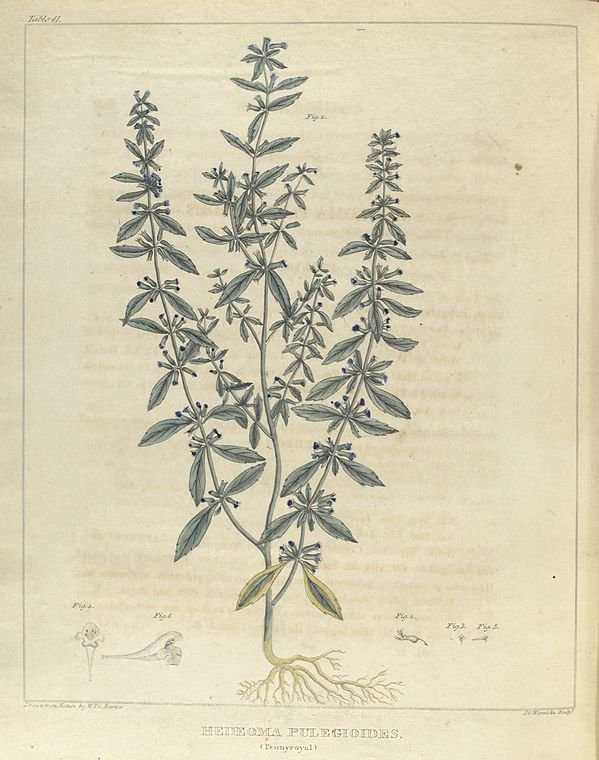

States in the U.S. were beginning to restrict access to abortion by the 1820s. This article from Duke University posits that for centuries women were using poisonous plants to abort fetuses, and these methods often killed the women themselves. Connecticut was the first to introduce laws banning this type of birth-control method, imprisoning women for life who attempted to abort after the first “quickening” of a child, or a fetus’ first movements in-utero. In the 1850s the American Medical Association began it’s campaign to outlaw abortion, and in 1869 the Catholic Church formally condemned abortion at any stage in pregnancy.

The introduction of the Comstock Law in 1873 was a blow to reproductive choice as well. These laws prevented the distribution of contraceptives and information about contraceptives across state lines or in the mail, making it much harder for folks to get access to family planning aids. In 1913 Margaret Sanger, a nurse and activist, coined the term “birth control” and was indicted for violating the law. A pioneer in reproductive rights activism, Sanger was instrumental in the fight for birth control access.

Although Sanger’s influence is unquestionable many questioned her other convictions. She allied with eugenists and often spoke about a need to control family size for Black and poor populations. Although her contemporaries argue that working with eugenic thinkers was an alliance of convenience, others remain convinced of her racism. Anti-abortion activists often cite her involvement with racist organizations to discredit all of her work and the pro-choice movement in general, I believe this to be a false equivalence.

In 1916, Margaret Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in Brooklyn, and is again arrested for violating the law. This clinic would eventually become Planned Parenthood.

In 1951, Sanger begins working with a scientist, Gregory Pincus, to develop the first oral contraceptive pills. These pills are a modern miracle: a great leap forward for reproductive healthcare. In 1960 Enovid is the first FDA approved contraceptive pill, although 30 states still have Comstock laws forbidding the dissemination of these contraceptives or information about them.

This wouldn’t be the status quo forever, Griswold v. Connecticut ruled that married couples had a right to contraceptives as a part of the universal right to privacy.

This important precursor to Roe v. Wade established a precedent that paved the way for abortion and contraceptive rights and access in the United States.

In 1967, Connecticut is the first state to pass laws allowing for abortion in cases of incest, fetal defects, or mental health reasons.

By 1968, several birth control options become available globally and by 1970 Hawaii legalizes abortions at the request of a woman or her doctor, followed by New York, Washington, and Alaska.

In 1972, the Supreme Court rules in Eisenstadt vs. Baird that the Massachusetts law that prohibits the sale of contraception to unmarried women is unconstitutional.

The 1973 Supreme Court case, Roe v. Wade, grants the universal right to abortion in the United States under the constitutional right to privacy.

Although it would seem that this victory led us towards a shining future, there was backlash to the win presented by Roe v. Wade and attacks against abortion and other reproductive rights continue today. Abortion rights continue to make strides forward and take steps backward in the decades following Roe. Reproductive freedoms remain highly debated.

Attacks on access to birth control include bans on federal funding for abortion, separating it from healthcare costs. There were attempts to require the signed permission of a woman’s husband or a minor’s parents in order to gain access to abortion. Waiting periods were introduced, requiring those requesting abortion to wait for a predetermined amount of time before the procedure can be completed. Barriers like this persist in this country and compound in order to make abortion totally inaccessible in some parts of the country and for our most marginalized populations.

repro in living color

Intersectionality presents oppression as intersecting, and necessarily our view of the reproductive justice movement and history must be intersectional. While women like Margaret Sanger and others were fighting primarily for access to contraception and abortions, Black women were fighting a two-sided battle for the right to contraceptive care AND against sterilization.

Since the 1920s, eugenic sterilization programs were running in more than 30 states in the United States. These laws targeted Black, Brown, poor, disabled, and immigrant women for forced sterilization on the grounds that they were mentally unfit to have children. Often women would go to the hospital to give birth and be sterilized without their consent while there. For Black women in the American South the procedure became so common it was known as a “Mississippi Appendectomy”. Of the 7200 people sterilized in North Carolina between the 1930s and 70s, 65% were Black women.

The 2015 film, No Más Bebés, revealed the systematic sterilization of monolingual Latina women in the 1960s and 70s at USC Medical Center in Las Angeles County. In the midst of labor they were coerced into signing forms for tubal ligation, going to the hospital to have their babies and leaving sterilized without their consent.

In 1937, Puerto Rico passed laws that allowed for access to contraception and sterilization at the discretion of a eugenic board. From the 1930s to 1970s, approximately one-third of all Puerto Rican women on the island were sterilized due to this decision.

This 2017 article examines the “voluntary” sterilizations that continue in Tennessee prisons. Inmates have been offered reduced sentences and other perks for volunteering for this program. This is a part of the long history of sterilizations within prisons in this country, which the article details further. Many debate the capacity of incarcerated folks to consent to such procedures when they are in no place to reject them.

This information doesn’t mean that people of color, poor folks, disabled people, and so many others were not fighting for the right to access abortion and contraceptives. It mainly meant that these folks held a more critical understanding and nuanced viewpoint when it came to reproductive rights and freedoms. While fighting for the right to family planning and healthcare access, they were also fighting for the right to have babies and reproduce, something many white, upper-class, privileged activists didn’t have to think about.

In the Summer of 1989, Black women banded together to create a public statement. “We Remember: African-American women are for Reproductive Freedom” was a groundbreaking pamphlet given out at anti-sexual assault rallies, anti-apartheid demonstrations, and other gatherings. It was endorsed by some of the most powerful Black women in the country, like Rep. Maxine Waters, Shirley Chisholm, and Dorothy Height. Black women called for their rights, advocating for their ability to make choices about their health and bodies as well as the right to do so as pushbacks against abortion persisted on a state level.

These Black women activists had felt that their voices were going unheard within the pro-choice and reproductive rights movement and wanted to speak to their constituency; Black women who were in need of abortion access and healthcare, those who were getting abortions but were too ashamed to speak up and speak out. There are a myriad of reasons why Black women specifically sought abortions detailed in the pamphlet, and an equivalent amount of barriers keeping Black women from accessing abortions and other healthcare. Those issues continue today as we really begin to acknowledge the reproductive rights activism of folks from all walks of life, their specific needs, and how we should act to bring an intersection lens to our repro activism.

the fight continues…

In September of 2021, the Texas Senate enacted Bill 8, a new law that outlaws access to abortion after a fetus’ heartbeat is detectable. For most this is the 6 week mark in pregnancy, and realistically that’s before many would even know they are pregnant. This creates a problem for Texas abortion providers as it is coupled with laws encouraging Texans to report and take their neighbors to civil court if they suspect they have undergone or aided someone else in accessing an abortion.

In states where access to abortion is already limited, this bill creates an incredibly dangerous model that other states are intending to follow, creating loopholes that circumvent Roe v. Wade. Access to abortion has already been curtailed by state laws, the underfunding of abortion clinics, the threat of violence, and other barriers; this may be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

When it comes to access, especially for our most marginalized citizens, abortion is already banned in practice. Time restrictions on abortion, like the 3-day waiting period required by some states, means that folks traveling out of state for an abortion, like Texas residents, would have to make arrangements for travel, work, school, and have money readily available for a long-weekend stay miles from their homes. A 6-week ban would mean that most pregnant people would be only 2-weeks late on their period and unable to save or prepare for these expenses in addition to the cost of an abortion. 37 U.S. states require parent/guardian notification before a minor can receive an abortion, and this restricts access for many underaged people. Outside of these restrictions money, travel, and notification can restrict abortion access, making it incredibly difficult for those in the United States who lack wealth, Paid-Time-Off, transportation, and support from accessing abortion.

There is so much that we can do to aid in the fight for reproductive rights in our hometowns, and I would advise each and every one of us to do some research on the reproductive healthcare providers in our area. In addition there are most likely abortion funds functioning in your area, or in Texas where folks are desperately in need of help, that we can contribute our dollars towards. The one thing each and everyone of us can do is attempt to provide information, support, and advocacy when we can to the people in our lives who need abortion and reproductive healthcare access.